As a 20-year-old student I am statistically set to boycott the general election in May alongside 2 million other young people. As a nation we are constantly concerned with the fact that young people are not engaged with politics, and that we can’t determine why. The Hayward Gallery’s most recent exhibition ‘History is now: 7 Artists take on Britain’ attempts to highlight the inadequacies of our recent political history, whilst accidentally mirroring the tediousness of understanding and engaging with British politics.

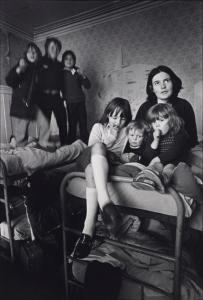

Between the honesty of Christine Voge’s photographs of London’s first women’s refuge centre from 1978, the accumulated documentation of the women’s peace camp at Greenham Common from 1983-84 and the loneliness in Mona Hatoum’s film “Measures of distance” from 1988, the general consensus of Jane & Louise Wilson’s section was that politics has failed women. Or at least it would have been had the curators thought to focus their space rather than overwhelm the audience with such a broad history of British politics. In some ways including the multitude of unconnected narratives was effective at highlighting the spectrum of political failures but ultimately this was too much to tackle in such a small space. The shame is that the pieces that focused on women created such a strong narrative, which was only compromised by the inclusion of too many others.

The selection of black and white arts council collection photographs presenting dark truths of the 70’s to the 90’s in comparison to the colourful columns of advertisement collages from the same era in Hannah Starkey’s curation made for an obvious

comparison. It was strange that John Hilliard’s quadrant of photographs “Cause of death” (1974) was tucked in a corner, or that it was shown at all. This piece concisely proves the objectivity of photography as a medium, demonstrating through 4 examples that the way images are cropped, shot and composed can completely change our interpretation of a narrative. Showing this powerful statement next to so many other photographs was jarring, as ultimately Hilliard’s piece renders all other images around it as objective depictions, so therefore it is impossible to read Starkey’s desired curation of propaganda vs. truth in this space.

Despite coming from the madness of Roger Hiorn’s mad cow disease research, it was actually John Akomfrah’s curation that finally made me give up on the exhibition. Consciously choosing to show 17 films with a total running time of over 500 minutes, Akomfrah effectively cuts off communication with the audience before a conversation can even be started. Although inconvenient and aggravating, this does feel rather appropriate. This unrealistic demand echoes in concept what is asked of young people when it comes to politics, where we are asked to vote into a system that time after time proves to us that it doesn’t work.

This exhibition, in parts, does uncover the failures of recent politics and the fact that it coincides with the lead up to the general election is interesting, but if this is so important, where were the politicians? Addressing the public with such an overwhelming depiction of political failures seems pointless when the over riding sentiment of the exhibition is that politics needs to change, not the people.